It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that Orlando Wilson is a man who lives and breathes training. In this article, he draws on his own personal insights to give a detailed account of the challenges encountered when operating training programs in foreign countries, often in far-flung areas of the world.

It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that Orlando Wilson is a man who lives and breathes training. In this article, he draws on his own personal insights to give a detailed account of the challenges encountered when operating training programs in foreign countries, often in far-flung areas of the world.

Based on his considerable knowledge and experience as a trainer in security procedures, Orlando has synthesized these 14 lessons on how best to deal with situations, which are rarely encountered in the Western world.

JFK Airport, New York. Waiting to catch a flight to the Middle East where I will give a seminar for members of a National Police Force, I begin to pen this article.

During this trip, I will stay in a nice hotel, be chauffeured around and paid a decent sum, but all this is a far cry from 25 years ago when I was a 17-year-old recruit reporting for basic Infantry training at Depot Litchfield. Over the years I have provided security and training services to a wide variety of private and government clients in Western and Eastern Europe, US, Latin America, and Africa. Every job and each location come with their own individual problems!

1. Be Diligent

The first thing I take into consideration when approached for a contract is who the clients are and if they are times wasters, which 90% are. Also, I want to know what it is they want, and if they can afford it. I regularly get emails from people asking about a vast array of requests with money not being a problem; these tend to be the dreamers and the wannabes. When I believe someone is a serious client then we need to confirm they are who they say they are.

Several years ago I was approached by a police training institute in Mexico, where my company and I have worked numerous times. We were at the stage of waiting for the plane tickets to arrive, luckily for us they did not. A week or so later we saw the media reports that the institute had been raided and its officials and others associated with the local police had been arrested by federal police because of connections to the Drug Cartels. These days you have to be very careful, especially when operating in countries where government corruption is high!

2. Be Resourceful

When I write proposals I expect that the training programs will change if we get the contract due to facilities, equipment, personnel, or local politics. But if the flights and retainer are in order, we deal with the expected issues when we get to the location and the training starts. What a lot of people don’t realize is that running commercial training projects and operating outside of a regular military or government structure is very different. For a start always remember, if things go bad for whatever reason, you have no support. Your local embassies will do the minimum they are required to do at a time when you really need their support and assistance.

3. Be Realistic

One of the big issues that a lot of inexperienced trainers have is that they expect living conditions in a developing country to be the same as they are in the U.S. or Western Europe. But this is simply not the case. One job in Mexico, we were staying in a police barracks and my associate had a scorpion nest in his room and I had a rat in mine. We also had to be careful when leaving our rooms to make sure the free roving rottweilers had been chained up!

Things that people take for granted like power, internet and gyms may be limited or non-existent. While I was working in West Africa, electricity and power could be on for maybe a couple of hours a day, so laptops were always plugged in, phones charged at every opportunity. In most locations internet is available to some extent, so you need to see how the locals get it and make sure you’re not getting scammed on rates. Food can be another big issue for some trainers; don’t expect the luxuries of home such as steak and potatoes. If trainers and operators are fussy eaters or germ-phobic, it raises a red flag for me. To be able to operate effectively, you need to be comfortable in that environment!

4. Be Adaptable

Training programs often change because the facilities and equipment that were requested or expected are not available, so you have to work with what you’ve got. In locations where there are issues with corruption, you can expect problems with equipment being stolen or sold. On one job I ended up cutting a deal with a team leader of a tactical team on ammunition, as the allocation kept getting smaller without a shot being fired. I understood their situation but my main concern was improving the operational effectiveness of the team and for this, I needed the cooperation of the team leader and the team members.

5. Maintain Perspective

At the other end of the scale, we once had a group on a custom-built course in Serbia. This group included two American instructors who had a law enforcement background. They stayed in the most expensive hotel in Belgrade, yet they still managed to complain about the facilities – a serious dose of perspective was needed. They would say; “In America, the ranges are better”, “in America we were given new Glocks for the students”, “In America…” These supposed experienced instructors were ignorant and prima donnas and could not understand how the rest of the world is not like America!! In America tactical equipment, guns and ammunition are freely available and quite cheap, but not so in most other countries.

6. Show Respect

I am lucky that over the years I have had some good guides and I remember one from when I was in South Africa in 94 who made it clear to me you must respect and understand others cultures. He was white and of a British Army background and it was clear to me that his native employees respected him greatly. He told me how he’d made it clear to his guys from the outset that culturally, they were ‘chalk and cheese’ and that they operated in a different manner to how he did. But, he also made it clear that he respected their culture and expected the same in return. It worked!

Behavior is extremely important; people seem to forget that when on training and operational projects. Those paying your wage will watch you closely. Big problems can arise when people make statements about politics or the performances of local police or military commanders and start stepping on toes. Many instructors seem to forget that they are guests and that the local order of things always needs to be respected, even if it’s not to your liking.

7. Understand the Regional Politics

The general rules for behavior should be that you want to be as anonymous as possible. Show maximum courtesy to your clients and always respect the local culture and bureaucracy. Also knowing the local laws and limits of your responsibility is extremely important. Backstabbing and jealously exists in all aspects of the security business and sources of this need to be identified. In locations where there is a lot of internal bureaucratic power struggles going on, people will be looking to trip up your project just to belittle those who contracted you for the job. On one job in Mexico, we were called to meet the local police commissioner who told us he did not want us there as his superior had brought us in without his knowledge.

One incident I had while working with the vigilantes in Nigeria resulted in a Mexican standoff between us and the army. The army and police chiefs for the area were informed there would be armed vigilante patrols operating. But within minutes of us hitting a paved road, army patrols appeared wanting to confiscate firearms and make arrests. The vigilantes are community security teams where the army and police are federal organizations and have a greater authority. I understand this was a part of the local power struggle and the soldiers were just hoping for bribes. We had anticipated this problem but what complicated and infuriated me was that the person in charge of the project who had met with the police and army chiefs and who we had on standby was delayed in getting to our location. And the reason was that he was hungry and sent his driver to get beer and food, so he ended up getting a taxi!! Never expect those in the rear to realize or want to get involved in the issues that can arise in the field, even if they can talk a good war, don’t expect them to get their boots dirty!

One incident I had while working with the vigilantes in Nigeria resulted in a Mexican standoff between us and the army. The army and police chiefs for the area were informed there would be armed vigilante patrols operating. But within minutes of us hitting a paved road, army patrols appeared wanting to confiscate firearms and make arrests. The vigilantes are community security teams where the army and police are federal organizations and have a greater authority. I understand this was a part of the local power struggle and the soldiers were just hoping for bribes. We had anticipated this problem but what complicated and infuriated me was that the person in charge of the project who had met with the police and army chiefs and who we had on standby was delayed in getting to our location. And the reason was that he was hungry and sent his driver to get beer and food, so he ended up getting a taxi!! Never expect those in the rear to realize or want to get involved in the issues that can arise in the field, even if they can talk a good war, don’t expect them to get their boots dirty!

8. Set Clear and Appropriate Expectations

Now to me, the actual training of the students is the easy part of a training contract. Because as you can hopefully see by now that just getting to day-one of the course can take a lot of planning and politics. So when it comes to training the students, you need to clarify what they really want and how hard they want to be trained. You may think that if people are paying for a training course they want to be trained to the max, not always so. When working in Latin America and Africa the students tend to want to be pushed hard and learn as much as they can. In the U.S. people tend to expect coffee, lunch breaks and to work a 9 to 5. This is where you need to work with the clients and see how they want training, they are the ones paying the bills. It used to frustrate me that if students did not want to train hard then they were not serious and not going to be up to a decent standard. These days I see it as their choice, as long as they are happy and I get paid, I am happy. I remember taking one individual in Florida for a private pistol class and this guy was shooting poorly even though he had a very expensive firearm. When I tried to correct him he kept telling me that he had always shot the way he was shooting and did not listen to my advice. If people want to pay me and not listen to my advice then that’s their choice. You can’t educate pork, but as long as they pay cash I am happy!

Now to me, there is a big difference between lectures and training courses. Some things you cannot teach solely by showing PowerPoint presentations and videos. It makes me laugh that a lot of close protection courses, especially in the U.S., are made up of nothing more than lectures, BS exercises in parking lots, some basic shooting and maybe a controlled trip to a restaurant. With our civilian courses, our student-run realistic exercises, and on our government courses, all exercises, where possible, are live. This is the best way for people to learn and it also exposes them to some of the potential problems and stress of live operations.

9. Identify and Delegate Leaders

On the larger training contracts, the student instructor ratios can be high as there is not the budget for more than a couple of instructors. When working with the vigilantes in Nigeria I usually had 60 students for 12 days courses. Initially, I had to delegate to the district leaders to organize their people until I could select guys I could use as instructors. Those I tended to choose were those who generally had the most punishments during their courses and took it with a smile. It’s easy to teach techniques to intelligent people but finding intelligent people who can take and give out punishment is another thing. Nigerian vigilantes tend to be a bit rough around the edges and need to be dealt with in ways they respect!

10. Earn Respect

That said, you must always show respect to your clients and students. Some trainers have a superiority complex and seem to think that just because they are from a developed country that those from developing countries are stupid. This is a big problem and can lead to a lot of issues, especially when the trainers start to be shown up by their students. I have trained students over the years who were illiterate and did not own shoes but spoke multiple local dialects and could survive indefinitely in the bush with only a machete–skills I can only dream of having. In Latin America, I have worked with those that don’t own a piece of brand name “tactical” equipment but understand the streets better than the criminals they deal with every day. I respect my students and over the years have learned a lot from them.

If you do not have your students respect then you are going to have problems. If you cannot do or have no operational experience at doing what you are teaching, then how can you expect your students to respect you. There are many instructors who are purely instructors and know what they have been taught and read but know nothing of the problems of applying these theories on operations. Just as there are many students who have plenty of operational experience but have never received any formal training. They know BS when they hear it because they already know what works and what doesn’t work, that’s why they’re still alive.

11. Don’t Forget The Basics!

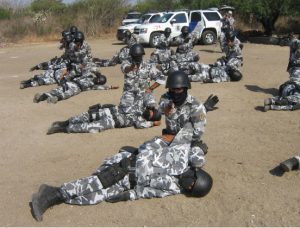

I have dealt with tactical teams trained by the British, French, Americans and even the North Koreans and what is always lacking are the basics. Everyone seems to want to show the high-speed entry techniques but forget about the basics like how to read a compass and approach a target location without detection. I remember one Mexican team who had received several months training from French and U.S. agencies, they looked pretty, stacking up outside of a door, but had no procedures for dealing with offensive actions by the criminals. So, they were being taught procedures from countries where the criminals are very tame and compliant and then trying to employ these procedures against very aggressive, motivated and trained drug cartels. Needless to say, things were not working for them… Again, you must understand the threat environment and opposition you will be training the students to deal with.

12. Train For The Real World

I like to identify the general fears of those I am training and exploit them–be it swimming rivers in the dark or standing between targets during live-fire drills. This exposes the real character of the students and incorporates stress into the training, which is essential when training those who will be working in high-risk areas. Safety must always be considered, but in my opinion in places like the U.S. people are more worried about a student breaking a nail than being operationally effective. When training serious students who will be using the skills taught, they tend to understand cuts and bruises go with the turf.

When running intense courses for government agencies in high-risk locations we train the students hard; long hours, minimum breaks for food and constant activity. I am not one for the “positive re-enforcement” method of training where even if people are screwing up they get told how good they are. This is used in a lot of U.S. law enforcement training and the theory behind this is that the cop just needs the confidence to deal with the situation even if they are not that competent. This is acceptable in low-risk locations like the U.S. and Western Europe, but when dealing with serious criminals I would want to be working with people that are competent and not those who just think they are competent. There is a big difference!

13. Training Is For Making Mistakes

On all my courses I like my students to make mistakes and to take them outside of their comfort zones. Anyone can talk like a perfect tactical guy in Starbucks. Students learn more from making mistakes and this also helps them see what they have been doing wrong. I tell my students it is far better to make the mistakes during training rather than on operations. I have come across some people that cannot handle having their faults identified and being constructively critiqued. This is just ego and insecurity issues on their part. I remember one operation that was carried out by vigilantes in Nigeria that was a complete fiasco and I am glad to say it was nothing to do with me. They had good intelligence that several known kidnappers were staying in a village, a reconnaissance was done and identities confirmed. The operation was led by the area coordinator who had no training and would not go through my courses. He gathered a group of about 30 vigilantes and drove straight to the village with the vehicle’s sirens blazing, just like in the movies. Needless to say, the kidnappers escaped and the guys I had trained were disillusioned with the coordinator’s actions. This operation was outside of my scope of responsibility, but sometimes it’s funny to sit back and let people show their true worth!

The first time we worked in Mexico we were training a state police tactical team and to say they had attitude and ego issues would be an understatement. After about 3-days straight training, resulting in one of their guys ending up in hospital and the team commander almost being shot accidentally by one of his own team, they started to listen. There was another team that had to be shown room entry techniques but had never trained to work as a team and had no discipline. We were with them 16 days in total and by the end; they were a very effective team. Maybe too effective…

14. Discipline and Punishment

Discipline is something that many people are lacking and it’s not something that can be installed through lectures. There has to be consequences for incompetence and punishing the whole group for one person’s stupidity usually leads to the group educating the wrongdoer. Outside of the U.S. and Western Europe, fighting and violence during courses are a lot more common, especially when the students are tired, hungry, etc. Discipline needs to be enforced and in some situations, it can quickly lead to violence, this again, goes with the turf.

Problem-students need to be identified and if they are not able to comply with the program then they need to be dismissed. This can lead to issues if the dismissed student has influential friends and then the politics begin. In such situations, my usual compromise for the dismissed student to be let back on the program is for them to complete a task that will take them outside of their comfort zone.

Summary

Hopefully, you can see from this article that there is more to running a training program than just teaching lessons. The main problems come from organization, planning, and politics. It’s clear to see that providing commercial training and an operational service is a lot different than working for a government agency or the military. There is a lot more to take into consideration and you have little or no real support. Crucially, you need to understand the culture and politics of those you’re training, and most important of all, you need to get paid!

14 Lessons For Running Training Programs in Foreign Countries

By: Orlando Wilson

Orlando Wilson has worked in the security industry internationally for over 25 years. He has become accustomed to the types of complications that can occur when dealing with international law enforcement agencies, organized crime, and Mafia groups. He is the chief consultant for Risks Inc. and based in Miami but spends much of his time traveling and providing a wide range of kidnapping prevention and tactical training services to private and government clients.

Leave a Reply