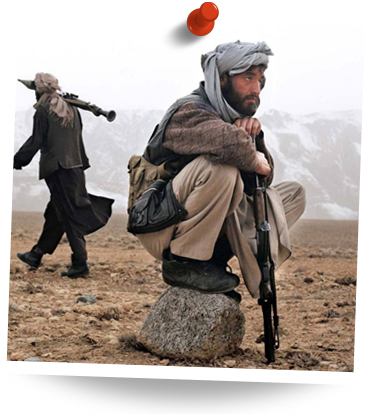

Afghan Endgame

OEF – Why it failed and what next…

After more than a decade of bloody operations, is it finally time for NATO to concede defeat on the battlefield and switch tactics?

Operation Enduring Freedom – The chaotic legacy of the Bush administration outlives its architect and wears on into a tenth year. Hard now, though it may be to remember but the operation enjoyed unparalleled global support at the time of its inception, in response to the 9:11 terror attacks on New York. Now, a decade on and without an acceptable conclusion in sight, the powers of the Western world must look towards a change in tactics to effect a viable solution.

“Who are we to surge 30,000 more troops into the graveyard of the great?”

Alexander the Great

Where did it go wrong?

OEF has been fought through three marked phases, each conspicuous by their level of troop involvement, casualty rate and public support. They can be categorized as follows:

- Phase 1 – Air domination and intelligence gathering.

- Phase 2 – Hearts and minds.

- Phase 3 – Surge policy.

The first two are undoubtedly orphans of the previous administration but phase 3 is wholly the creation of the Obama administration, a Frankenstein’s monster of a policy torn between achieving its aim and appeasing the voter.

The strategy of surging troops on and off a battlefield results in high collateral losses with short term territorial gains before ultimately a morale sapping relinquishment of initiative. In such a scenario we concede the ability to dominate strategic areas of importance effectively and simultaneously. Instead troops become reactive and defensive, which can then be exploited by an integrated and well motivated enemy. Nevertheless this has been the method employed and the argument over its effectiveness wrangles back to the days of Alexander the Great when he debated “Who are we to surge 30,000 more troops into the graveyard of the great?”

During periods of de-surge the dynamics alter allowing insurgents to move onto the front foot, presenting the opportunity to clear and recapture strategic land. The psychological boost which this generates, contributes highly toward the altering of consensus amongst the local population and subsequent changing of allegiance.

As long as the will and desire to fight remains then the insurgents will ultimately prosper unlike their foreign occupier who is limited by time and political pressure from the homeland. The Taliban are unburdened by time and the patience, where necessary to sit tight and wait for the right opportunity. As war intensifies so do civilian casualties leaving blood on the hands of the international military and every innocent killed becomes a recruitment drive for the insurgents.

“As for the United States’ future in Afghanistan, it will be fire and hell and total defeat, God willing, as it was for their predecessors – the Soviets and, before them, the British.”

Mohammed Omar

Foregoing the perceived logic, the theory behind a surge strategy has always been a risky one. It is based on the premise that in one fowl coordinated swoop the insurgents would be either killed or flushed out of their strongholds. International forces would then secure strategically important areas of the land before handing over to Local National Security Forces who would then carry on the task of enforcing law and order.

Unfortunately, this model was never going to work in Afghanistan and for several reasons:

The numbers committed to the surge, whilst large, were never going to be enough for a country as vast and inhospitable as Afghanistan.

Neighbours with vested interests are having too much influence in the replenishment of arms and munitions and the recruitment of fanatics willing to die for the cause which they have been indoctrinated in.

Obama publicly stated that the timescale for the duration of the operation would be 18 months, largely to appease voters in the US. However, this boldness was to ignore the lessons of history which show, time and again, that Afghans are seasoned duelists and do not lack in patience. They will content themselves in holding tight and waiting months, years if necessary as they know that neither the US, nor any other foreign occupier can endure such a long campaign. Again, history serves up many examples of this, look to the British, Russians and Romans in Afghanistan or consider the US war in Vietnam, the current deployment in Afghanistan has already waged longer.

Other important factors which make the task of ridding Afghanistan of radical extremists difficult, include; endemic corruption, ill equipped and undertrained security forces, tribal politics and Western economical considerations. Yet, it is geography which is the key factor in the battle to secure Afghanistan. It’s borders are too porous, too mountainous and too hostile for NATOs underwhelming strength to maintain. The hand over of key areas from ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) to ANSF (Afghanistan National Security Force) has not worked and under the radar, mostly to avoid embarrassment and a public outcry, ISAF forces have been reoccupying locations that had previously been entrusted back to the Afghans. This has foiled military planners efforts to make the host country responsible for securing its own borders and assuming control.

“The best thing we could have done for Afghanistan was to get out of our Humvees and drink more green chai. We should have focused less on finding the enemy, and more on finding our friends.”

Craig M. Mullaney, author of ‘The Unforgiving Minute: A Soldier’s Education’

So, if plans A, B and C have not worked despite a decade of attempts to the contrary then what option does that leave? Whisper it quietly but it is negotiation are where hopes are being pinned. Many who once rubbished any prospect reconciliation being the key to success are now laboring hard to create lines of communication between all parties. This might be perceived as failure in some quarters and it would be hard to stomach, in particular for the families of the thousands who have given their lives trying to secure an outcome under a different strategy but would any of them wish for more blood to be spilled unnecessarily? History documents evidence of a further harsh reality, which is: conceded negotiation is invariably how most guerrilla warfare ends.

Without doubt there is still plenty of work to be done before an effective compromise can be brokered. Yet, with the West and in particular, the Americans, sticking to their timescale for withdrawal it would seem as though the International consensus is that peace in Afghanistan cannot be realised through military intervention alone or perhaps at all. Have the lessons of history finally been understood?

“We will not be a pawn in someone else’s game, we will always be Afghanistan!”

The defiant words spoken by Ahmad Shah Masood, Afghanistan’s National hero during his battle for victory over the Russians.

Jon Moss

Leave a Reply