This article will cover:

- Why casualties need to be kept warm

- How we normally keep warm and how casualties lose heat

- What can be done to minimise heat loss

Why casualties need to be kept warm

As warm-blooded animals, we keep the core temperature of our bodies remarkably constant at 37.5oC. This so-called “thermoregulation” allows the body to work efficiently and carry out metabolic processes at a controlled rate. Too hot, and the processes accelerate (any chemical reaction will become more vigorous with increased temperature) and we can suffer heat illness – the subject of a future article. If we’re too cold, the heart can develop irregularities of rhythm, the body can increase oxygen demand through shivering, and the blood becomes less able to form clot. This last factor is critically important for the trauma casualty when blood clot is needed to seal the blood vessels where they’ve been damaged. Less clotting activity means more bleeding, which means a poorer outcome for the patient.

How we normally keep warm and how casualties lose heat

The exact relationship between poor clotting and hypothermia is not clear but we know that cold trauma casualties are associated with a worse outcome than those whose core temperatures are near normal. Most medical systems work hard to maintain the core temperatures of trauma casualties. This is challenging in hospital, but even more so in the field, particularly in an operational environment.

We keep warm by several ways, most being impeded by major trauma. Some are behavioural and some are physiological. Examples include:

- Shivering. Increased muscular activity generates heat. In trauma where the airway or breathing may be compromised, this means muscles compete for now limited oxygen with vital organs such as the brain or kidneys.

- Seeking shelter. Not possible for most serious trauma casualties.

- Putting on warm clothing. Again, may not be possible for the injured.

- Moving around. Heat generated again through muscular work. Many casualties are immobile through injury, shock or pain.

- Limiting contact area with cold surface. A casualty lying on the ground has much greater contact area with the ground through which to lose heat, compared to someone stood on their feet.

Medical evidence shows that trauma casualties get cold, irrespective of the season and even in hot climates. The deployed medic has to work hard therefore to keep his or her casualty warm.

Heat is lost through a number of ways including convection (passage of cooling air around the body); evaporation (heat removed from the skin as water or sweat is evaporated from it); conduction (through direct contact with a cold surface); and radiation (energy directly radiated from the body). The smallest component is usually radiation, so reflective foil blankets have a limited action in reducing heat loss by this means. Most foil blankets have a greater effect by reducing heat loss through evaporation and convection, i.e. by acting as a wind-break, as they tend to be polythene-based.

What can be done to minimise heat loss

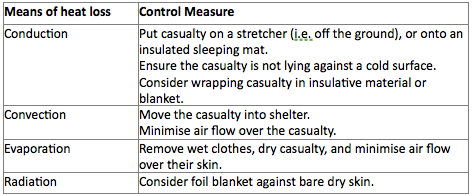

When looking after a casualty, consider the different ways that heat can be lost and deal with each as the situation allows. The table shown gives some examples.

Various pieces of equipment are available commercially which have different roles for different environments. Examples include generic foil blankets (lightweight and compact but of limited value); foil/absorbable casualty bags (some with a separate active heating blanket as well, such as the North American Rescue ‘Hypothermia Prevention and Management Kit’ – the HPMK); and insulation-orientated bags like the Norwegian LESS Thermal Bag and Thermal Hood (essentially made from a ‘bubble-wrap’ material).

Summary

Whatever your role in casualty management, remember the key points:

- Trauma patients get cold.

- Hypothermia in trauma occurs even in warm climates.

- Casualties who are hypothermic bleed more.

Keeping your casualty warm goes way beyond managing their discomfort. It is about trying to optimise their chance of survival, so consider it early and manage it well.

Dr Malcolm Russell

MBChB DCH DRCOG MRCGP FIMC RCS(Ed)

Managing Director Prometheus Medical Ltd,

and Clinical Lead for the Kent, Surrey & Sussex Air Ambulance

Leave a Reply