Cardiac Arrest can happen at any time, to anybody. Yes; some people are at higher risk of cardiac arrest with certain medical conditions or co-morbidities but very occasionally it ‘just happens’.

In 2013, in England alone, the ambulance service attended approximately 28,000 people suffering an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. The survival rate to discharge from hospital is only 8.1%. It is known that early cardiac arrest recognition, early Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), early defibrillation and early advanced life support from trained professionals are the key factors in the chain of survival.

CPR is crucial. If a cardiac arrest patient receives bystander CPR, their chance of survival is about 1 in 5. If they don’t receive bystander CPR, the chance of survival is less than 1 in 20. Basic Life Support (BLS) training is something we’ve all undertaken as part of maintaining our employment skill set. It is widely accepted that these skills diminish over 3 – 6 months after initial training. Therefore, it’s worthwhile refreshing these skills on a regular basis so that, if we ever find ourselves in the position of having to administer BLS to someone suffering from cardiac arrest, we can feel confident that the treatment we provide offers the patient the best chance of survival.

In this article, we will go back to those basics with a recap on the principles of Basic Life Support.

The Principles of Basic Life Support

The most important thing to remember is the three S’s.: Safety to Self, Scene, and Survivors – in that order. Hazards and dangers may not be apparent immediately so be cautious as you approach. If it is not safe then withdraw until help arrives.

Check for a response. Shout as you move closer. Then as you arrive at the patient’s side, gently shake their shoulder and ask them if they are alright. If the environment allows, call for help immediately. Ask for someone to fetch a defibrillator if one is available.

We continue with the <c>ABCDE approach. Never forget catastrophic haemorrhage in a cardiac arrest situation. If you do, then it will be ‘game over’ as soon as you start. Control any visible catastrophic haemorrhage before looking at the airway. Once controlled, move on.

Check The Airway

Look, clear, open and maintain an Airway. Visually inspect inside the mouth. Clear any obstruction (debris or fluid) you can directly see. This may involve turning the patients head and sweeping out the obstruction with your finger. Never perform a blind finger sweep. Only do this if you see an obstruction.

Simple ways of opening an Airway include the head tilt, chin-lift manoeuvre. This provides a clear open airway by moving the tongue from the back of the mouth allowing air to pass through into the lungs. This technique should be (where possible) avoided in traumatic cardiac arrest and a jaw thrust should then be used if you have been trained. These techniques have been discussed in previous articles. For those of you that have been trained in airway adjuncts such as the Oro-Pharyngeal Airway or Naso-Pharyngeal Airway, then now is the time to insert one.

Check For Breathing

Now your patient has a clear airway you must look, listen and feel for breathing. Keeping the airway positioned and open, place one hand on the patient’s chest and lean down to listen at their mouth to see if they are breathing normally. This should be done for a maximum of 10 seconds. If the patient is UNRESPONSIVE and NOT BREATHING NORMALLY, commence CPR. Your patient is in cardiac arrest. It is important to recognize that agonal breathing, often described as gasping, is a sign of cardiac arrest.

The above process will take less than 20 seconds if there are no immediate dangers to yourself, the scene or your patient. It is important that you now summon appropriate help. Call the emergency services and try and establish if you have anyone available to get access to a defibrillator. You now need to start cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Performing CPR

Start with cardiac compressions. Place the heel of your interlocked hands onto the centre of the patient’s chest. Press firmly down on the sternum (breastbone) approximately 5-6cms deep. This should be at a rate of 100-120 times per minute or twice every second. Ensure that you allow the chest to spring back into place between each compression. You need to perform 30 compressions. Then you need to give 2 rescue breaths.

When breathing for your patient, you can use mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-mask. If you have been trained with Airway adjuncts then you possibly may have been trained with mask ventilation. Ensure you have achieved an open airway with a head tilt, chin lift (in traumatic cardiac arrest, this may be your only option if you do not have a face mask for ventilations), and then provide your patient with 2 breaths by pinching their nose and blowing into their mouth. Continue then with compressions and breaths at a ratio of 30:2. Keep interruptions to chest compression to a minimum.

If, or when, someone arrives with a defibrillator, and they or you are competent to use it, then attach it as soon as it arrives and follow the instructions. Continue with CPR once it is safe to do so following defibrillation.

Only stop CPR if any of the following occur:

1. It is too dangerous for you to carry on.

2. The patient shows signs of life by regaining consciousness. This would be coughing, opening their eyes, speaking, moving AND they must be breathing effectively.

3. Help arrives and somebody appropriately trained takes over or asks you to stop.

4. You are physically exhausted and can no longer carry out CPR.

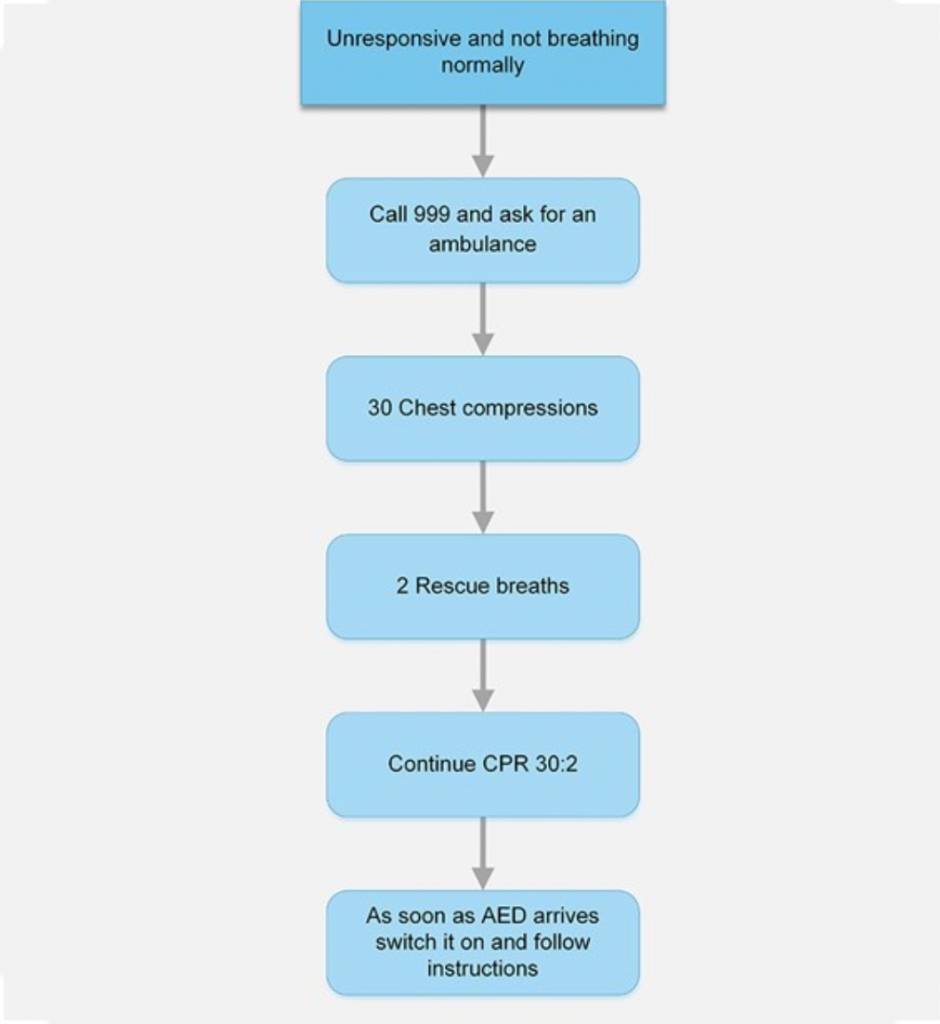

The flowchart, produced by the Resuscitation Council (UK), offers a simple algorithm to follow during adult cardiac arrest. It is advisable to read and refresh yourself with this algorithm as frequently as possible, as you never know when you will need to use it. Regular refresher training every six months will ensure your skills remain current and improve your ability to manage a medical emergency.

Basic Life Support

By: Kate Owen

Kate Owen is one of Prometheus’ Senior Instructors and has over 16 years’ experience working with the UK ambulance service. She currently works as a HEMS Paramedic.

Leave a Reply